A couple of years ago many of us became experts in engineering our prompts to get the best results from LLMs (like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini) for our research and evaluation projects. And we were (rightly) super proud of our new skills.

If you’re like me, over the last year you’ve likely hit the "uncanny valley" of AI outputs — I'm thinking, the response is fine, it’s grammatically perfect and even follows my instructions, but it doesn't sound like me. It doesn't quite grasp this specific evaluation framework, or what I'm trying to say, or it doesn't fit to my audience.

But how could it? How is the AI supposed to know that?

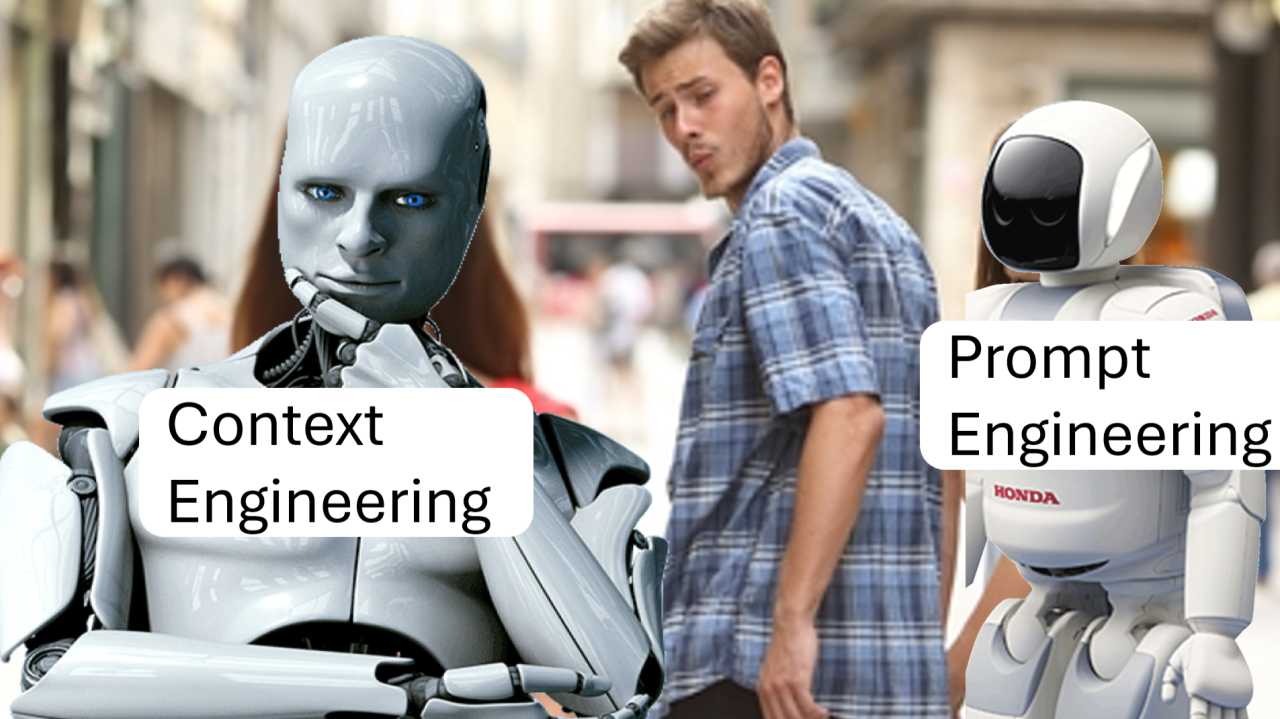

In a way you can solve this with better Prompt Engineering. You have to paste into your prompt a page or two about who you are, and another about how you write, and who you are writing for ... But in practice, for serious social researchers, prompt engineering is no longer enough. The future is Context Engineering — at least for the next few months...

Prompt Engineering vs. Context Engineering#

- Prompt Engineering is about the instruction: "how" you ask the question. You have a brilliant research assistant and give them a single-page brief for a task they’ve never heard of.

- Context Engineering is about the environment. It’s the "what" the AI knows before you even open your mouth, like giving that same assistant a permanent desk in your office, access to your previous five years of reports, your house style guide, a good idea of your quirks, and the full history of the project.

As qualitative researchers, we know: context is everything. Meaning isn't found in a vacuum; it’s found in the relationship between the data and the world around it. Context engineering is the deliberate act of building that "world" for the AI.

So how to I get to be a context engineer?

Four Levels of Context Engineering#

I think this is happening at four levels: from the manual "library" to the cutting-edge (and occasionally controversial) automation tools.

1. The Manual "Library": Markdown & Structured Files#

The most reliable way to start is by moving away from long, messy prompts and toward a library of text files. If you're keeping up, all the cool kids have been using Markdown (.md) files for this for some while now. If you're new, there's nothing to fear: Markdown files are just text files, where you can add a few simple things like stars to make the text look nicer. If you don't like markdown, just use any old system to store and keep track of your texts. The point about actual text files is that they are universal and don't get you stuck in some proprietary format or database that you can't access two months later.

Instead of typing every time some variant of "use a professional yet empathetic tone," you maintain a folder of context files, for example:

-

Style_Guide.md: Defines your specific "voice" (e.g., "Avoid academic jargon; use active verbs; prioritize participant agency"). -

My_Project_Background.md: Contains the theory of change, key stakeholders, and previous evaluation findings. -

Audience_Persona_Funder.md: Outlines exactly what a specific government department cares about.

By feeding these specific files into the AI alongside your task, you ensure the background information is accurate and the style is baked-in. At this stage, the "engineering" just means, keep a systematic set of files, and paste them at the bottom of your prompt when you need them. Ideally, you'd have a system which would sense which files you need and paste them in automatically without you having to worry about it...

2. Generic apps#

Most of the generic apps like ChatGPT now have a basic way to record this kind of knowledge as "memories" or similar. You can dig into the settings to see what. But it's fairly basic.

The app silently uses some version of RAG to automatically find which of your context files might be relevant. This is true for Steps 3 and 4 as well.... (thanks to Salvador Bustamante Aragonés for pointing this out.)

3. Gemini’s Nested Memory#

We are seeing a shift in the platforms themselves — most notably with Gemini’s new nested memory architecture (currently rolling out in the US).

Previously, "Memory" was just a flat list of facts. Now, if you are lucky enough to live in the US in 2026, haha, Gemini allows for a more sophisticated hierarchy — you can set "Global" memories (your bio and general research philosophy) and "Nested" or project-specific memories. This means the AI can distinguish between your "Evaluation of a Youth Program" context and your "Academic Journal Article" context without you having to re-upload files every single time.

4. The Automation Frontier: Obsidian ... and the "Clawd/Moltbot" Furore#

Now it gets a bit messy. If you use Obsidian for your notes, you are sitting on a mine of content — and context. Obsidian is great as a way of managing your text (Markdown) files. Personally I love that kind of stuff. For example, our causal mapping Garden is just a view of our Obsidian files. I'm writing in Obsidian right now.

- Obsidian Plugins: Tools like Smart Connect allow you to automatically inject context from your notes into your AI queries. You can essentially say, "Draft a summary of this interview using the context from every note tagged #Methodology." The great thing about this kind of stuff is that you are in complete control. Some Obsidian plug-ins also help you find relevant context files, e.g. using RAG. But automation is great too...

- IDEs: Tools like Cursor let you work with context text files and do pretty much everything you want with AI, including context engineering. I got Cursor to write a proof-of-concept "thematic analysis" paper which involved it editing and updating its own context files.

- The "Clawdbot / Moltbot" Scandal: You may have seen the recent headlines (Feb 2026) regarding Clawdbot (now renamed Moltbot / OpenClaw). This is a viral tool designed to give Claude or other LLMs "agency" to act across your files. While it showed the power of deep context integration, it also exposed massive security vulnerabilities.

The real frontier is these tools editing their own context files. Some of them have automated "dreaming": during down-time, drifting through the files and re-organising them: second-loop learning.

The takeaway for us as researchers? We want the power of "AI that knows me and knows my projects," but we must be incredibly careful about data privacy, especially with sensitive participant data. The "furore" serves as a reminder: context engineering is powerful, but it must be built on secure architectures.

PS

Silva Ferretti invites us to think about who we are / what we know / what we know how to do — and how much of that can be packaged up for an AI. I guess this will be an asymptotic process (ever nearer, but never completing) on the one hand we want and need to do that, on the other hand it's frightening ....

PS, Slight rant, slightly off-topic:

(I'm a bit sick of reading people complaining about how the AI failed to guess something it could never have known because someone didn't tell it. Like, in one context you assume it will be super liberal and progressive in what it says, and the next moment you criticise it for being too liberal and not representative of the whole population of the planet — don't get me wrong, there are REAL SERIOUS issues about the WEIRD AI world view, but at least make sure you tell it what you expect...)